History

By Nick Haggarty.

“Most politicians seek to manipulate the media to a greater or lesser extent. That is part of exercising power.” – Michelle Grattan, 1981.1

There is not a great deal of history recorded on the Press Gallery, and what there is has generally been written down in studies looking at how the press relates to the Parliament rather than the history of the Gallery itself. So it would appear that the Press Gallery has been much better at recording the history of the nation than recording their own history. What follows are some of the more important, interesting, scandalous and humorous events that have occurred in the reporting on federal politics since federation, and how things have changed over that time.

Edmund Barton

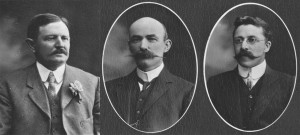

Three members of the first Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery, notable for covering federal politics before the first Parliament had sat, from left: David Maling, George Cockerill and Gerald Mussen. Photos: State Library of Victoria.

“Even before the Federal Parliament sat, there was a wealth of political incident to report. To Sydney in December 1900 came Lord Hopetoun, the Commonwealth’s first Governor-General, and the composition of the first Federal Government was determined there during the following weeks. A smaller group of senior journalists assembled in Sydney and reported the ‘Hopetoun Blunder’ (the Governor-General’s blunder in choosing the New South Wales Premier, Sir William Lyne, to form the first Ministry) and the ultimate installation of Edmund Barton as founding Prime Minister. Among them were journalists who rose to prominence in the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery: George Cockerill, David Maling, Harry Peters, Gerald Mussen.”2

Victorian Parliament House, Melbourne

This photo is of the first federal budget in 1901 and is the oldest known photo containing the members of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery. They are seated in the gallery above the Speaker’s chair. The picture also shows one current and five future Prime Ministers – Barton, Deakin, Cook, Reid, Watson and Hughes. Photo: National Library of Australia nla.pic-an23312255

The history of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery dates back to 9 May, 1901 in Melbourne with 31 journalists covering the first sittings of Parliament. Between 20 and 32 journalists worked between the years 1901 – 1927 when the Press Gallery was located in the Victorian Parliament House where Federal Parliament sat. There were just three offices for journalists there – two for Melbourne newspapers The Argus and The Age, and the third was for interstate journalists, most of whom were from NSW. (The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald are the only two organisations who have had representatives in the Press Gallery since 1901.) Incredibly, there was space for the interstate scribes located on the floor of the House of Representatives chamber while ministers (apart from the Prime Minister) had no offices in the Victorian Parliament. Reporters had ready access to Prime Minister Edmund Barton who lived in an attic in the Parliament.

“Interstate journalists could use the parliamentary telegraph room where operators with hand-operated Morse Code keys despatched their cables at public expense. (Longer reports were taken by messengers to the GPO.)”3

George Reid

“He [Prime Minister George Reid] had the full appreciation of the value of publicity. He once chaffingly said to a group of newspaper men: ‘Praise me if you can, blame me if you must, but for Heaven’s sake don’t leave me alone.’ He could not live upon his salary as a member of Parliament.”4

Alfred Deakin

In the Melbourne Federal Parliament it was possible to stumble across a story in a way that journalists today can no longer do. In the early years of federation Australia had no Navy, relying on the British for providing and maintaining vessels which cost the Australian government £200,000 a year. One morning Herald journalist Bert Cook arrived at work to receive a message – “The Prime Minister has been asking for you.” Cook was surprised because the PM, Alfred Deakin, had never asked for him before but when the Prime Minister asks for you, naturally you ring him.

“There was a telephone in the press room which was actually only 20 feet away from the desk in the room across the passage where Deakin sat at his desk. The telephone girl immediately switched me on to Deakin.”

‘Cook speaking,’ I said in a matter of fact way, ‘Understand you want to see me.’

‘Oh, yes. It’s about that Naval agreement. I’ve been thinking the time is about ripe to give the necessary notice of termination to the British Government.’

“I immediately realised that the Prime Minister thought he was talking to his colleague Mr Joseph Cook [later Sir Joseph, Australia’s 6th Prime Minister], the then Minister for Defence.”

‘Excuse me, Mr Deakin, ‘ I interrupted, ‘This is Cook of the Herald.’

“The dead silence could almost be felt. There was, however, that one little click one can hear when a telephone mouthpiece is quietly replaced.” – B.S.B. Cook, 1910.5

“Journalists often took political snapshots in the days before literary and photographic work were more sharply delineated. Bert Cook carried a small camera in his vest pocket so he could photograph Cabinet ministers at their desks.”6

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Every Press Gallery journalist now carries a camera in his or her pocket in the form of a mobile phone that can take a photo and upload it online instantly. The line between literary and photographic work has again become blurred.

Although Australia’s second Prime Minister was never a member of the Press Gallery, before Deakin entered federal politics he was a journalist. Given the number of former journalists who have become federal politicians, there is nothing extraordinary in Deakin’s rise through the ranks. Where Deakin’s story differs is from the moment he accepted an offer from the editor of London’s Morning Post, secretly becoming a federal political correspondent for £500 a year. For almost 14 years Deakin wrote for the Morning Post and also for the London National Review. Over those years he was also Opposition Leader, Minister For External Affairs, Attorney-General and on three separate occasions was also Prime Minister! Deakin’s pieces were written with an insight that a Press Gallery journalist could only dream of, and, by all accounts were relatively free of bias.

Andrew Fisher

Like Prime Ministers before and after him, Andrew Fisher had to contend with the issue of leaks from his Cabinet to the press. Nothing annoyed him more than to discover that confidential Cabinet discussions had been conveyed to members of the Press Gallery and he took the issue quite personally.

“There was the occasion when I walked past the room of the PM in the public offices opposite Melbourne’s Treasury Gardens. My shadow had fallen across the frosted glass panels. Within a few seconds the door suddenly opened and Fisher glared up and down the corridor. I asked [Secretary for the Prime Minister’s Department] Shepherd what Fisher was looking for. He replied that Fisher was annoyed and irritable at the leakage of Cabinet secrets, and hoped to catch the spy”.7 – Bert Cook.

After the First World War broke out in July 1914, the Parliament passed the Federal War Precautions Act in October that year, an act that meant the Department of Defence oversaw official censorship of newspapers.

“Almost immediately the Press Gallery, editors and proprietors conformed but bristled with frustration at the political interference, domineering bureaucrats and self-serving government handouts that amounted to nothing more than blatant political military propaganda.”8

Billy Hughes

During the war years… Press Gallery jobs in Melbourne were highly prized and the pay was superior, though the hours long.9

Many politicians have two distinctly different faces; the one that they show the public, the other that is only seen by those who are in contact with them day-to-day. While Prime Ministers have been concerned with their public images, at times obsessed with how they appear to the community, the person that the members of the Fourth Estate gets to see may be vastly different.

“Access to Ministers, including the Prime Minister (Billy Hughes in my time) was regular and easy. We usually saw the Prime Minister twice a day and were able to ask any questions – unless he happened to be in one of his tantrums.” – Ralph Simmonds, 1966.10

While some Prime Ministers have been quite apologetic in instances where they have kept people waiting, others have seemed to not care about keeping the media waiting.

“Journalists on the round…swore that his [PM Billy Hughes’] deafness increased or decreased according to whether he wanted to hear a question or not; sometimes blandly indifferent about the long hours of waiting to see him.”11

Suspensions, Bans and Imprisonment

The media has always been a part of Parliament House since Parliament first sat except for a brief time in Melbourne when interstate journos were kicked out. In 1914 a Parliamentary committee moved to restrict the movements of journalists in the Victorian Parliament building which a few journos took offence to. The journalists concerned responded by pinning a list of the committee members’ names to noticeboards within their offices with titles such as “The Lousy List” with the intention of giving them “no free advertising” and “no favours”, effectively no newspaper coverage of their speeches and dealings in Parliament. When the presiding officers of the day found out and inspected the journalists’ offices they responded by kicking out the offending organisations until an apology was promptly given.

In 1914 the House Committee ordered that a caricature of Gallery members on the wall in a press office be painted over. What was once regarded as graffiti would now be preserved as an artwork.

There have been a couple of incidents where individual media have been banned from Parliament House. One of these was in 1931 where journalist Joe Alexander was banned for five months from the House of Representatives and its precincts after publishing leaked material that was embarrassing to the then Scullin Government. During those five months he was still allowed in the Senate Gallery to report but would have to stay on the Senate side of Parliament House, not able to cross an invisible line down the middle of the building. Alexander could often be seen standing on the Senate side of that invisible line frantically waving in the direction of Members as they left the chamber to get them to come over to him for a chat. Another incident in 1955 involved two men, businessman Raymond Fitzpatrick and reporter Frank Browne, who breached Parliamentary privilege and were brought before the bar of Parliament. [From Rob Chalmers’ account, “They came through the main door of the house from King’s Hall accompanied by the Serjeant-at-Arms. At the entrance to the chamber itself there was a horizontal metal bar, placed across the end of the passageway, and they each in turn stood at this bar, directly facing the Speaker, Archie Cameron. The house was packed for this historic injustice. ”12] The men were not allowed legal representation and both were subsequently gaoled for three months, a power that Parliament has not exercised since. The Press Gallery, as well as politicians from both sides were outraged that people could be gaoled without a trial or the opportunity to appeal the conviction or sentence. In 1967 a minister complained that journalist Maxwell Newton was not doing “bona fide” journalistic work. He was a freelancer and newsletter writer, and eventually left the Press Gallery under pressure the following year.

“It is by willingly receiving and publishing leaked information that journalists may play a very active part in the political process.”13

Stanley Bruce

Pressers, Doorstops, Interviews and Briefings

The terms press conference (or presser), doorstop, briefing and interview all refer to a politician/s speaking with members of the media. A press conference is usually quite formal with the speaker standing behind a lectern or sitting behind a desk. Doorstops are so named as they used to occur most often at the entrance to Parliament House where politicians would stop at the door to speak to the gathered press. They are less formal than press conferences. Interviews are usually where one politician is speaking to one journalist, the content of which may or may not be exclusive, and briefings are not open to recording devices but are for background information. The assumption is that information given on the record may be readily disseminated by the interviewee’s opponents and is therefore accurate to the best of their knowledge. However, there was occasion when Prime Minister Stanley Bruce started to give off the record information that was false, ending up in him being confronted by a pack of Gallery reporters where he was handed a smack down.

“You have the right to refuse to answer any questions, but if you give us guidance off the record, we are entitled to expect it not to be misleading. We would rather have no information than misinformation. We have noticed lately a tendency to mislead us.” – Cecil Edwards, 192314

Starting under Prime Minister Stanley Bruce in the 1920’s, journalists would gather once or twice a day to meet with the PM, often in his office. These days journalists meeting with the Prime Minister in the same way are rare. On an ordinary day press conferences will only happen once with the Prime Minister, and when a big story has broken after the PM has already spoken, often one TV camera will be allowed access for a statement which is then distributed to all media.

The last day of sitting of the House of Representatives in the Victorian Parliament House, 24 March 1927. Once again the members of the Press Gallery managed to get themselves in this photo of Lower House politicians. National Library of Australia nla.pic-vn4503539.

“Ministers did not have press secretaries and rarely issued press statements. Instead, Ministers and departmental heads were accessible to regular Federal roundsmen [journalists with specific reporting areas], talked freely and trusted the press completely. There were no press conferences of a formal kind, but the Prime Minister usually saw pressmen at fixed times – before lunch, in the afternoon, and sometimes in the evening at Parliament House when Parliament was in session.”15

In 1927, former PM Billy Hughes welcomed the departure from Melbourne: “The powerful press of Melbourne, moulding and moulded by public opinion in that great city, exercised a profound influence on Parliament.”16

Provisional Parliament House, Canberra

“Press Gallery journalist Joseph Alexander observed that “Ministers and public servants seemed more human, easier, relaxed and accessible” in the new parliament. In Canberra and at Parliament House they all had a different social life as they were all from somewhere else, forced by circumstance and isolation to mix together; including the PM. This proximity to Bruce allowed journalists to reflect on the personality and character of an incumbent PM. They could now judge the mood of the man more closely than ever before and the stress and strain on his government.”17

The first journalists to arrive in Canberra in May 1927 for the opening of the Provisional Parliament House, or Old Parliament House as it’s commonly known, received a very Canberra-like welcome in the form of the weather. Visitors to the ACT who are unaccustomed to the low temperatures will often complain how cold it is, and the press were no different. However, far from what today’s tourists experience, when they can stay in a vast array of heated accomodation, the journalists had to endure the freezing conditions in tents.

Unlike the Victorian Parliament building, which was never designed to cater for Federal Parliament, Provisional Parliament House was specifically designed to house federal politicians but the original designs allowed space for just 48 occupants in the Press Gallery. Given that the journalists in the Gallery in 1927 numbered in the mid 20s, it was shortsighted to cater for only an extra 20 or so people joining over the coming 50 years that Parliament was to sit in the provisional building.

In the early years in Canberra the only paper that was based locally was The Canberra Times, so reporters of all the other papers had to get their stories out to their head offices any way they could. They would send their reports via press cables lodged with the parliamentary post office or sent to the nearby GPO by pneumatic tube (when it didn’t jam) to be sent to Sydney or Melbourne by Morse Code operators. Some reports were phoned through while others that were not urgent were sent by train.

During his six week election campaign in 1925, PM Bruce delivered 71 speeches, visited most state capitals and covered 10,000 miles (16,ooo kilometres). He was the first to electioneer by plane, taking three journos on the campaign trail in 1929 when he lost. Modern election campaigns are huge events involving two busloads of traveling media (one with the Prime Minister, one following the Leader of the Opposition) as well as local media covering stories as the traveling parties come to town. The media fly across the continent several times over a campaign usually arriving just before or just after the leader they are following. Journalists used to fly on the same plane as the PM or Opposition Leader during a campaign, a significant advantage in learning background information on how their election was going.

“Mr Bruce was very much more the polished Parliamentarian who maintained a gulf of official reserve between himself and the journalists.”18

James Scullin

Prime Minister James Scullin recognised the importance of publicity of his ministry and directed his ministers, wherever possible, to give copies of second readings of bills to the press before ministers had read them in parliament. He also understood the value of avoiding multiple stories being released on the same day and of regular drip-feeding of information to the Gallery to achieve the widest coverage.

Scullin was the first PM to regularly speak on radio, and the first to take journos into his confidence. This happened only once, during the Great Depression. Six months after becoming Prime Minister he stopped reading the papers whose journalists and editors were critical of him. So bad was this criticism that it sapped his confidence to read the news, a flaw which would prove fatal to his understanding of and dealings with the media.

J.A Alexander on the first confidential briefing from a PM (Scullin) during the worst of the depression years: “No Prime Minister had ever done such a thing before. This fact, and the grave, almost distressing demeanour of Mr Scullin at this meeting made a profound impression on those who participated in this conference. All emerged from that meeting with a new sense of responsibility. I think that day marked one of the turning points in the history of the Gallery.”20

Sometime around Scullin’s time as Prime Minister, journalist Reg Leonard was working late one night recording the debates in the press gallery of the House of Representatives chamber. Then he fell asleep.

“Awakening in darkness, he moved towards the three steps leading up from the gallery and instead stepped over the ledge of the gallery and then over the top, narrowly missing the spikes of the Speaker’s chair and landing beside it. Extraordinarily, he was uninjured…” – Allan Fraser, 1976.21

Also uninjured after an incident years later in the mid 1960’s was ABC journalist Les Love. Love was reporting in the Senate press gallery one night after a tipple too many when he fell off his chair and brought several more chairs down with him “uttering an ear piercing howl of surprise and agony”.22 The Senate stopped, Love reappeared and it was back to business as usual.

Joseph Lyons

The start of one of the biggest political stories in Australia’s history occurred in 1931 but it was missed by a number of Press Gallery journalists. Nearing the end of a sitting day, two journalists heard that Joseph Lyons was leaving Canberra that night on the train. At the time Lyons was a senior minister in the Labor Scullin government and it didn’t feel right to these two journalists that he should be leaving in the middle of a sitting week (these days it is quite normal for a minister or the PM to catch a plane after a sitting day, make an announcement or give a speech in another state and fly back for the next morning’s sitting). With a bit of digging, the journalists in the know had their story in less than an hour, one of them racing to the train and jumping on, happy to alight anywhere with a fantastic yarn. Meanwhile their colleagues went home and were scooped by the story of the year – Lyons was resigning from the Labor Party. This lead to Lyons forming the United Australia Party, which not only beat Labor at the next election and ruled for a decade, but eventually folded into the Liberal Party of Australia.

“The man assigned to this work has to be alive to every pulse-beat in the Parliamentary body, able to detect the slightest trace of abnormality, able to sense that things are going wrong, that something is out of tune, that somebody is ‘up to something’.”23

The Press Gallery likely worked harder and longer during Scullin and his successor Joseph Lyons’ reigns than at any other time since federation. Journalist Warren Denning wrote that 20 hour shifts were common, 40 hour sittings of the House of Reps were frequent and “on one occasion we went for 56 hours without sleep or a break; eating our meals at the House and carrying on in a daze.”24

As happens in many workplaces, long hours and hard work often leads to tempers being frayed. Add to those ingredients a personality that grinds on others and the perfect storm brews. The Daily Telegraph’s Massey Stanley was one who put noses out of joint as Allan Fraser had experienced several times before the following incident occurred.

One day the unforgivable word passed between Massey and me in the Gallery and we had to fight. We strode together in silence from the House to the small hill (since demolished) which was then a hundred yards from the building. There we fought on rough ground, each falling occasionally, until my nose at least was bloody and my eyes were black. Then without a word we broke it off and walked together, still in silence, back to the House. We had told no one of our intention yet the flat roof of Parliament House was crowded with spectators who had a grandstand view.25

Proprietors of media organisations have long held political biases. Whether these biases have successfully passed through to the reporting of the journalists or not, the management of media companies have nevertheless often held thinly veiled political ideologies. In 1934 before the federal election the general manager of the Brisbane Telegraph wrote to Prime Minister Lyons: “We are, of course, doing our utmost to create a favourable atmosphere for your party and I think our newspaper will play no small part in the forthcoming elections. In any case we shall do our best.” – L. Broinowski.26

As Canberra was a planned city built specifically to be the nation’s capital it took quite a few years before much more than Provisional Parliament House was in the Parliamentary Triangle. As a result, by the late 1930’s politicians and members of the Press Gallery tended not to venture far from work when socialising.

Prime Minister Joseph Lyons meeting with members of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery. Photo: On Message: Political Communications of Australian Prime Ministers 1901-2014 by Julian Fitzgerald.

“Politicians and reporters drank together, fraternised on the Parliament House veranda and went on picnics and fishing trips together. When they traveled interstate they went on the same train and stayed in the same hotel.”27

“…very often he’d finish up his press conference by inviting them into his ante room and having a drink with them.” – Irvine Douglas on Lyons’ relationship with Press Gallery journos.28

Lyons might have been on friendly personal terms with journalists, but he certainly didn’t like the criticism he received from them.

“Lyons found the burden of press criticism increasingly irksome. In a querulous mood about such criticism, he once asked (former PM Stanley) Bruce how he had coped with a hostile press. Bruce replied: ‘Oh, I never read the bloody stuff!’”29

Radio Arrives

Radio as a medium had been broadcasting into Australian homes for many years prior to the first representation by Gallery journalists in the field. Both Scullin and Lyons made radio broadcasts, with Lyons regularly using the wireless to speak directly to listeners without being edited by a newspaper journalist. ABC radio arrived in the Gallery in 1939 when 32 year old Warren Denning moved from being a newspaper reporter to covering radio. It came about after Prime Minister Lyons accused the papers of misrepresentation and his Cabinet invited the ABC to appoint a representative in Canberra. Despite having worked in the Press Gallery for nine years, Denning’s former colleagues didn’t take kindly to his new role as they were worried about the ability of the new medium to break stories well before newspapers went to print. On the insistence of the newspaper journalists, when Sir Robert Menzies first became Prime Minister in 1939 he held two press conferences a day, back to back – one for the newspapers and the other for Denning, as the print reporters didn’t want the radio reporter sharing in their information. Denning actually picked up a few exclusive stories by having a private daily meeting with the PM, a situation which went on for about six weeks until Menzies was fed up with it and held one press conference for everyone.

Respected print journalist, Alan Reid conceded that newspaper reporters were slow to adjust to the arrival of the “microphone reporters” and resented them.

“Once they started pushing microphones under a politician’s nose, I found we were moving into a second class area. They would talk to us on an off-the-record or background basis. When the microphone was poked under their bloody noses they’d give precisely what they’d given us, publicly. So the politicians were much faster in reconciling themselves to this media than the old print inhabitants of the Press Gallery were.” – Alan Reid.30

Years later the opposite was the case. In an interview in the late 1980s, legendary Nine Network reporter Peter Harvey complained “They’ll leak it to somebody who’ll print it so it can’t be sourced back to them. They’ll leak it on background but they won’t come anywhere near a microphone. This is happening more and more.”31

The first radio broadcasts of parliamentary proceedings began on 10 July 1946 on Radio National and are still broadcast today on ABC NewsRadio.

“The ABC, a government instrumentality, was ordered to undertake the broadcasting of what was widely believed to be the most turgid and boring radio broadcasts ever put to air.”32

Arthur Fadden

When he was Treasurer in the early Menzies’ Cabinets, Sir Arthur Fadden was described as perhaps the best source the Press Gallery had. Fadden liked sharing a drink with journalists and it lead to a few stories, some that could be printed and others that could not.

“…there were nights when Mick Byrne, his press secretary, and I had to arrange for the night porter at the Hotel Canberra to unlock a side door so that no one would see us helping the Deputy Prime Minister through the main foyer.”33

Some journalists have been instrumental in removing Prime Ministers from office. One of these reporters was Ross Gollan of the Sydney Morning Herald. During Menzies’ first term in the early 1940’s Gollan was critical of him and close to Country Party leader Arthur Fadden. When Fadden succeeded Menzies in 1941, Gollan enjoyed tremendous prestige as a king-maker. Unfortunately for Gollan though, his previously unheard of access to the Prime Minister’s office lasted only 40 days as the Country Party PM was ousted within 6 weeks of being sworn in.

“Mr Fadden was always friendly and helpful, ready to go to no end of trouble to see that journalists were not kept waiting about.”34

The issue of keeping the media waiting for a Prime Ministerial press conference or other event was to rear its ugly head during the years Kevin Rudd was PM. Rudd would often be up to an hour or more late to an appointment which frustrated the Press Gallery enormously, and it didn’t change after he won the office back from Julia Gillard in 2013.

John Curtin

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of the Curtin Family. Former journalist John Curtin meets the Canberra Press Gallery. (Known as The Circus) C.1945. JCPML00376/2. Curtin is seated and standing, from left to right, are Don Whitington (Daily Telegraph), Ross Gollan (Sydney Morning Herald), John Corbett (Argus), Frederick Smith (Australian United Press), Richard Hughes and Norman Kearsley (Brisbane Telegraph), T L Thomas (Australian United Press), Ted Waterman and Joe Alexander (Melbourne Herald), Jack Commins (Australian Broadcasting Commission) and Don Rodgers (Curtin’s press secretary). This copy courtesy of the Reid family collection.

Probably the closest relationship that has ever been forged between a Prime Minister and journalists was that of John Curtin and a group of men who became known as Curtin’s Circus. From December 1941 the Circus met regularly with Curtin, the meetings occurring regularly until the final months of the war when the PM’s health deteriorated. Whether Curtin was in Canberra or not, the men pictured on the right were part of his inner circle and traveled wherever he went.

“At 10:30 pm, Curtin leaned back into his chair wearily. ‘Well boys – anything further?’ The pressmen asked whether on some occasion he would take them into his confidence and describe the strategic situation. ‘No time like the present,’ he replied. Doors were shut, and the attendants excluded. Curtin talked till midnight. Most of the pressmen had been accustomed to hearing Menzies’ polished phrases and were still disposed to dismiss Curtin as a woolly rhetorician, but as they listened to his remarkable description of the world situation, given without notes, without hesitation, without the promptings of an expert at his elbow, they felt his greatness. By midnight all of them were exhausted but the journalists felt that the Prime Minister had revealed sources of great strength.”35

“The Prime Minister attaches great importance to the preservation of his confidence, while the roundsman of integrity would rather lose his left hand than break the Prime Minister’s confidence in him.”36

“Curtin had more faith in the integrity of the senior journalists at Canberra than any Prime Minister since, and probably any of his predecessors. A select band – he restricted his twice-daily press conferences to about ten or twelve heads of service – knew more about the secret history of the war than most Members of Parliament excepting the War Cabinet and the Advisory War Council.”37

Curtin was the first Prime Minister to employ a press secretary or media advisor, Don Rodgers on the far right in the photo above, and was one of only three politicians who had one at that time. Though some Prime Ministers before Curtin had people who would liaise with journalists on the PM’s behalf none had the title of press secretary.

Under John Curtin, the Prime Minister’s meetings with the Press Gallery would result in three categories of information. There were comments that the PM could be quoted directly on, information that could be attributed to a government source (but not ascribed to the PM) and information that was for background purposes only. Background information was not to be published but was given to reporters so that in the event they heard the same story from a different source they would know not to publish it. It allowed the journalists and their editors to be forewarned of big events, the best examples of which were stories of World War II operations.

“While you are sitting in the public galleries in the House you would notice men – and, during wartime, more and more women – moving about in the galleries opposite you in a way which may not appear to suggest a deep interest in what is going on. A few may be writing steadily; most are just listening. They whisper among themselves, move in and out, seem to find amusement in things which go over your head, behave generally in a restless way. These people are the Parliamentary journalists, the inhabitants of the Press Gallery; they know a great deal more about what is going on below than you are ever likely to know. Despite their apparent inattention, their ears and eyes are attuned to every momentary change of tone and tempo down on the floor of the House; although they rarely rush about yelling like Hollywood reporters, never have notebooks in their hands unless they be actually reporting the debates, they are among the two hundred best-informed political authorities in the country.”38

Ben Chifley

After Curtin’s death in 1945, arrangements between the PM and the media changed. Curtin’s successor Ben Chifley held pressers twice a week, not twice a day as the men of Curtin’s Circus had become accustomed to.

By and large, the good relationship that had been built between the Gallery and Curtin remained when Chifley took over, as journalist Stewart Cockburn recalled – “Most of the Gallery was very pro-Chifley because of his engaging personal qualities and these reinforced the Gallery’s natural sympathy with Labor. I was myself … a Labor supporter in the 1940s and 1950s and knowing that the Sydney Morning Herald did not love Menzies, I felt I had a licence to criticize and embarrass Menzies whenever I wanted to do so.”39 Cockburn would eventually go on to become Press Secretary to Menzies after he became PM.

“Like Curtin, Chifley trusted Gallery leaders with a good deal of confidential background information.” – L.F. Crisp, 1960.40

“[Journalists are] paid stooges who with pen and tongue and radio voice are prepared to sell the cause of truth and their own souls at a lesser price than that for which Judas sold his master – that is when one takes into consideration the increased cost of living since Biblical times.” – Ben Chifley PM41

Stranger Danger

Technically the Press Gallery has no right to be in Parliament House. There is no legislation that formally recognises the Gallery’s role and allows it to have a gallery in the chambers or office space in the building. The members of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery are classified as “strangers”.

“After all, the press has no right to be here. The only right the press enjoys here is the privilege bestowed upon them by the Parliament.” – Senate President Rosevear, 1947.42

“…no stranger has any right to enter the precincts of Parliament. He may do so only by permission. In that respect pressmen have no greater rights than are possessed by the poorest wayfarer who seeks permission of Mr Speaker to take a seat in the gallery… Everybody who is not a member of this Parliament is a stranger in this House.”43

The proceedings in the House of Representatives and the Senate have always been open to the Australian public with a few exceptions, such as debates on national security matters that occurred during wartime.

“The old formula used to be that a member told the Speaker: ‘I spy strangers,’ which at once required that steps be taken to exclude the strangers. Even the Press, which has a recognised, though not official, status inside Parliament, with all kinds of privileges, is completely subject to Parliament’s will and right to meet privately; and when on rare occasions secrecy is required, the journalists in the Press Gallery rise and leave in common with all others, except members themselves and the Clerks of the House.”44

Robert Menzies

When Menzies became Prime Minister again in 1949 he began holding two press conferences a day – one in the morning for the evening newspapers and one in the afternoon for the morning newspapers. But two press conferences a day quickly turned into once a day. He really didn’t like the press and was described as being cold towards journalists.

“Menzies came in and scarcely apologised for being late and then said ‘You know I loathe the Press’.” – Irvine Douglas.45

“His relations with most journalists were distant and patronising.”46

“Menzies always assumed that the 36 journalists in the Canberra Press Gallery, representing 18 news organisations were supportive of Labor after the war years and during the reconstruction of the nation [About 20 additional staff visited Canberra for sitting weeks]. He never expected them to be fair in reporting the public policy work of the government. Denied the opportunity to articulate his programs to the people through newspapers he went over their heads and used advertisements and radio broadcasts to deliver his political messages.”47

These days the Prime Minister’s media team are very conscious of how he/she is represented visually, but during Menzies’ rein he liked to call the shots himself.

“Menzies could be awkward, even discourteous, in his daily contacts with the press, and there were frequent complaints about his rudeness. During a visit to a Sydney dockyard in 1940, Menzies turned his back or put his hands over his face whenever a cameraman tried to photograph him.”48

“The public are very child-like: they like something that rattles. It is the age of publicity which means that the most illiterate of all trades, that of newspaper writing, becomes dominant.” – Menzies, 1941.49

Presented to the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery by the Right Honourable R.G. Menzies, October 1951 and signed “Who misreported me, anyhow? Robert Menzies 1951”. Left to right: Messrs. Elgin Reid (Courier Mail), Frank Chamberlain (Sun Pictorial), Hal Myers (Sydney Morning Herald), Ian Fitchett (The Age), Kevin Power (Daily Mirror), Jack Allsopp (Australian United Press), Gavin Handley (Sydney Morning Herald), Les Teese (Australian United Press), Irvine Douglas (Sydney Morning Herald), Stan Hutchinson (Sun Pictorial), Charles Nicol (Menzies’ Press Secretary), John Bennetts (Melbourne Herald), Fred Coleman (Argus), R Maley (Argus), Brian Wright (Argus), Jack Kenny (Daily Telegraph), Jack Commins (Australian Broadcasting Commission), Harold Cox (Melbourne Herald), Bob Logue (Daily Mirror), Gordon Burgoyne (Australian Broadcasting Commission), Alan Reid (Sydney Sun). The original hangs on the wall of the National Press Club, Canberra.

Within a few years of taking office for the second time, Prime Ministerial press conferences were rare. Often months would pass without contact between Menzies and the Press Gallery. It even got to the stage when journalists would arrange for an Opposition Member to put a question to the Prime Minister in Parliament.

“Under the post-1949 Menzies prime ministership, off-the-record meetings between pressmen and the head of the government had dwindled, then disappeared. By the Autumn of 1954, reporters in Parliament House seldom got to see the Prime Minister.”50

“The Sydney Morning Herald has always detested me, a detestation which I heartily reciprocate… Its leading articles contain in almost equal proportions testiness, pomposity, and a sort of bogus intellectuality which I find hard to bear. Unfortunately, they have a very considerable influence among my own supporters.” – Menzies, 1958.51

The Canberra Press Gallery despised, yet respected him and in recognition of the awe in which he was held, dubbed him with the popular title of “Ming”.52

The way that journalists interacted with politicians in the early 1950s was quite different to how it happens now. In 1951 there were only three people who had press secretaries – Menzies and two ministers. Nowadays every politician has someone as a contact point between the media and themselves and often the only way for a journalist to speak with a minister is to call their press secretary first, assuming the journo doesn’t have the minister’s mobile number.

“The ministers had to handle the press themselves—a great way for junior reporters to get to know them. Unlike present-day ministers, they were not shielded by spin doctors, and ministers such as Harold Holt were adept at press relations and knew nearly everyone in the gallery on first-name terms.”53

When Menzies’ press secretary was on leave, Charles Nicol was often seconded to fill in. Years later Nicol wrote about his experiences of the PM’s aloofness as it related to members of the Gallery:

When the House was sitting Menzies was adroit at delaying consideration of submitted questions until they were beyond the significance of edition times. Frequently he would defer seeing me until after the House rose late at night by which time the relevance of queries had lapsed and morning edition deadlines had passed.

In this way Menzies was able to interpose his Press Secretary between himself and the media on controversial publicity.54

Sydney Morning Herald journalist Fergan O’Sullivan had more than one master in 1951. Not only was he writing for the SMH but also compiled a dossier on some 45 Press Gallery journalists for the Russian embassy. In a time of tense relationships between Western and Eastern Blocs at the height of the Cold War, the scandal involving a spy within the Press Gallery was big news that reverberated for some time. O’Sullivan spent a short time as press secretary to then Opposition Leader H.V. (Doc) Evatt. It also emerged in the mid 1950’s that some journalists had been working for ASIO. At the time, Press Gallery journalists had to be members of the Australian Journalists Association (AJA) who were quick to suspend O’Sullivan’s membership. From the mid 1960s through to the 1980s at least 10 journalists were involved in espionage working on one side for the Russians or the other side for ASIO, and in some cases working for both!

The Provisional Parliament House building was a place where the relationship between journalists and politicians was close. An example of this closeness was journalist Alan Reid’s son, Alan Jr, being taught how to tackle by Opposition Leader Doc Evatt. It’s hard to imagine a similar situation occurring now.

“…he could be a hell of a nuisance…he’d think nothing of ringing you up at 2 o’clock in the morning to ask you what you thought on a certain subject…” – Alan Reid on Doc Evatt.

Struggles Between the Press and the Parliament

Up until the late 1940s media organisations paid rental of 1/- a square foot of office space. Converting that to decimals would be about $1/m2. In the 1950s the accommodation was provided rent free with the presiding officers arguing that any rent taken by Parliament would imply some sort of rights or status that they were unwilling to give. Rents for Press Gallery members were abolished in 1950 by Speaker Archie Cameron.

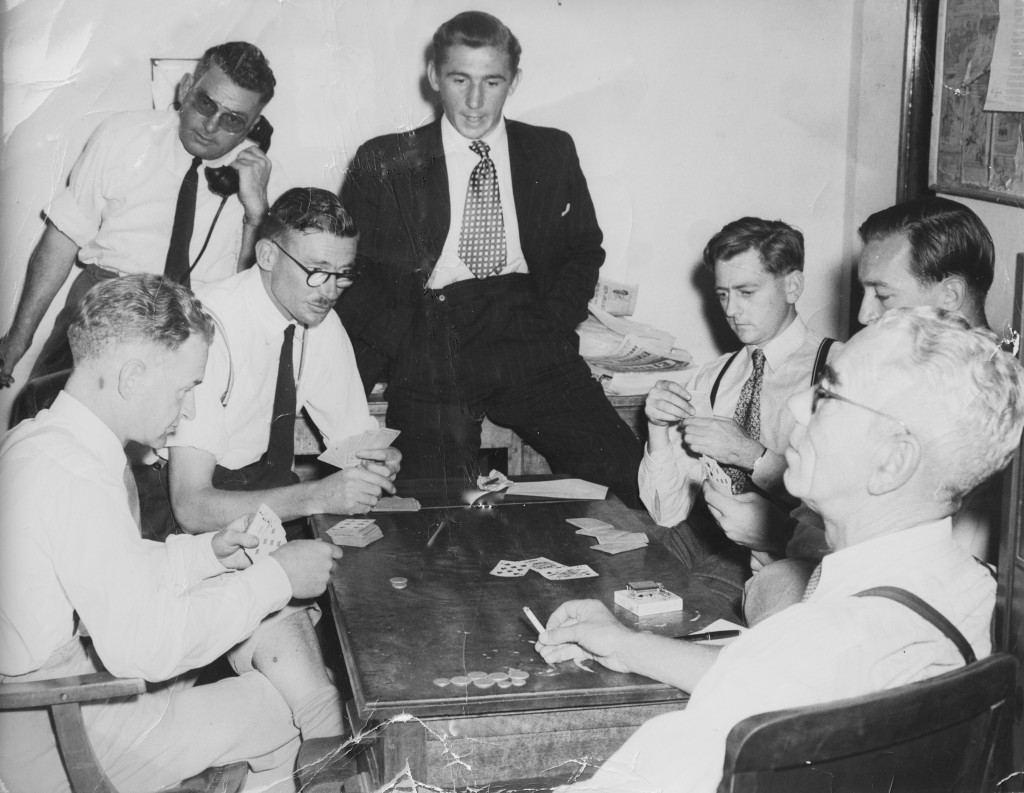

A group of journalists playing cards in the Press Gallery common room, circa 1950. The coins on the table suggest they were playing for keeps. Photo courtesy of the Reid family collection.

He also climbed through a window from the roof of Parliament House into the Gallery common room one time to find a group of journos on a break playing cards, then warned them that he would be severe in dealing with reporters in the future who misconducted themselves in Parliament House. After all, they were playing poker, and at the time gambling wasn’t allowed in the building. The ongoing struggle between the Press Gallery, politicians and the Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) sees regular stoushes with media being restricted in where they can go within Parliament House and what can be filmed, photographed and recorded. Generally, politicians of all persuasions don’t take kindly to negative press and those in power will do all they can to avoid it, even if it means restricting the media in their reporting. The media will push the boundaries at every turn and argue that some boundaries border on censorship. Parliamentary Security and DPS find themselves in the middle, policing and enforcing the rules on a resentful media. After Tony Abbott won office there were some changes with the way the media was handled at Parliament House. Previously, there were no physical barriers erected between the working media and politicians. Nowadays crews are kept behind bollards at various points outside the building and in committee rooms despite there being no incidents to trigger such an approach. It has resulted in a great deal of resentment from the Gallery towards Parliamentary Security, DPS and the government.

“The psychological relationship between newsmen on one hand and officials on the other is odd and interesting. I suppose it is almost a classic example of attraction – repulsion, the two parties simultaneously drawn towards and repulsed by each other, each trying to use the other, each trying to avoid being used by the other.” – John Bennetts, 1962.55

“All the journalists in the gallery were members of the AJA, the journalists’ union, and there were no photographers; casual outside photographers were hired for pictures.”56

Before cameras filmed Parliamentary proceedings it was possible for some pollies to get away with behaviour that could now be caught on tape. A keen eye and attuned ear sitting in the Press Gallery, however, would ensure that little escaped capture.

“[Labour member for Port Adelaide Albert] Thompson also had the misfortune to share a two-seat bench in the house with former coalminer and colourful character Rowley James, who held the seat of Hunter (in the Newcastle area) for 30 years from his election in 1928. Rowley was a large, rotund figure, and one could observe from the press gallery Rowley’s habit of leaning on one cheek of his arse to let go a roaring fart in Thompson’s direction. Albert would lean as far as he could into the corridor alongside him to escape the noxious gas. Following one of James’s louder farts, Eddie Ward was on his feet taking a point of order: ‘Did Hansard record the Member for Hunter’s interjection?’ he asked.”57

Alcohol consumption may not have played a part in the incident above, but it certainly did in the following story.

“One of the more spectacular drunken performances of the 1960s was in the Senate chamber, when Labor Senator from Western Australia Harry Cant found himself seriously drunk and trapped by a division. The doors were locked and the division required Labor senators to cross to the other side of the chamber, sitting in the places of the government senators for the count, while the government senator moved to the opposition benches. Cant was overcome by an urgent need to vomit. Looking around desperately, he came to a decision. Opening the desk drawer of the government senator’s desk where he was seated, he was violently and noisily sick into it.

When the division was over and the senators resumed their normal places, the government senator in whose place Harry had sat was understandably disgusted. The stench created by this extraordinary happening filled the chamber. He did not draw the President of the Senate’s attention to the outrage or make a fuss. Urgent action was required. All this had taken place in the full view of the journalists in the Senate press gallery and those in the public gallery. News of the outrage was soon all over Parliament House and journalists rushed to get the story. Medical practitioner Dr Felix Dittmer, a Queensland Labor Senator, had the answer. He denied Cant was drunk and ordered that an ambulance be urgently called to take Cant to the Royal Canberra Hospital, just across Commonwealth Avenue Bridge in Acton. Dittmer stated that Cant was suffering from an acute case of ‘renal colic’.”58

Federal Parliament was broadcast for the first time at the official opening of the 23rd Parliament, 17 February, 1959. Broadcasts of Parliament like this were very rare until the 1990s. Photo: W Pedersen. National Archives of Australia A1200, L30857.

Television Arrives

Mainstream television arrived in Australia in 1956 but took several years to take off in the Press Gallery. In the 1950s and 60s any television news coverage of federal politics was shot on film and had to be sent to Sydney or Melbourne by plane for processing, editing and transmission on that evening’s news. The time involved in this process meant that for an interview to make it to air that night it needed to be done by 11:00 am. Compared to the live broadcasts and digital editing of today, it was a painfully slow process. It was not until 1968 that the first commercial film processing laboratory was opened in Canberra and films were developed locally. In December 1958 Gallery journos provided a total of about 20 minutes worth of TV commentary on the federal election results. Today, four networks devote around 5-6 hours straight of live TV with sophisticated graphics and links to several locations around the country for coverage on election night.

Menzies was described as a superb performer on television who didn’t like the new medium and became terribly nervous before appearing on it.

“…He had more press conferences in his last six months than he’d had in the years before. He was quite willing to agree on the second or third time of asking. They regarded him as arrogant, but I remember another side…For all his public appearances he was never completely at ease.” – Tony Eggleton, Menzies’ press secretary, 1986.59

As early as 1965, journalists were complaining about the reporting of stories being too reliant on material that was boxed, the equivalent of today’s emailed media releases, saying it was too controlled. This type of non-analytical reporting is still happening now, although it can be argued as to what extent. And way back in 1948 a conference of Australian newspaper editors passed a resolution condemning the use of handouts and PR men.

Harold Holt

By the time Menzies retired in 1966, the relations with Press Gallery reporters and the PM’s office were in need of repair. Harold Holt had a completely different approach to journalists, much more like the Curtin and early Menzies years in the access the new PM allowed. He was more welcoming of the electronic media than his predecessors had been having his press secretary oversee the installation of equipment in Parliament House to help TV and radio. Holt’s office had improved lighting installed for the cameras and even a fake pen on his desk to hide a microphone linked to a tape recorder to assist with faster production of Prime Ministerial transcripts.

Media team covering Prime Minister Harold Holt’s Vietnam visit, 1966-67. Photo courtesy of Tony Eggleton, press secretary to four Prime Ministers: Menzies, Holt, Gorton and Fraser.

“I remember what a big deal it was when we did Harold Holt in 1967. That was the first time there’d been a half hour interview with the Prime Minister. The sort of protocol that everyone was trying to develop to meet the occasion! Rules of behaviour were invented overnight… who would be there to greet the great man when he came, a sort of dummy-run, he will walk in this door and we’ll take him here and you will be there and it will take him exactly two and a half minutes to get here. The contrast: now Prime Ministers come and go into a studio and nobody ever notices except the people doing the programme. This all happened in less than ten years.” – Robert Moore, 1976.60

“Holt was the first Prime Minister to take the media on organised overseas trips.”61

John Gorton

By the time John Gorton became Prime Minister the Press Gallery had expanded to a membership of 60 journalists, with about another 20 on sitting weeks, representing 40 news organisations.

“A sign of the changing times was the fact that John Gorton’s perceived ability to handle television was one of the reasons he won the leadership.”– Brian Johns, 1965.62

However, it was a short lived honeymoon for the new PM. Gorton used to brief journalists like Holt did, but on an irregular basis and would exclude journos from these briefings who had criticised him and other Ministers in a manner he thought was “offensive”. Gorton’s lack of willingness to hold formal press conferences and lack of confidence in front of the cameras led to his losing the reins as Prime Minister.

“Having been created by television, Gorton failed to appreciate that it was his own worst enemy, stripping him, through its relentless, impersonal coverage, of much of the mystique of office.” – Maximilian Walsh, 1979.63

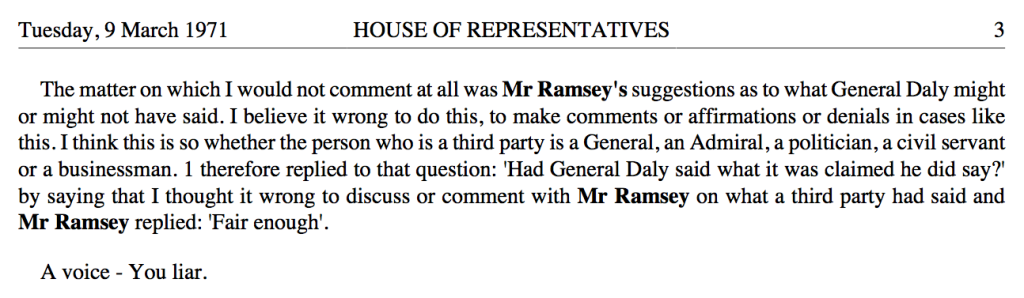

In the dying days of Gorton’s time in office a very public spat occurred between him and his Defence Minister Malcolm Fraser. It came about after journalist Alan Ramsey had met with Gorton to get an interview in relation to the incidents which brought about the rift with Fraser. Ramsey gave the Prime Minister a chance to repudiate a story about the army but Gorton refused to comment. A few days later Gorton gave his version of the meeting with Ramsey in the House of Representatives while Ramsey sat in the press gallery above. The PM’s version of events was not how Ramsey had seen it and the journalist was so incensed that he blurted out “You liar!” loud enough for the entire chamber to hear. Incredibly, Ramsey escaped repercussions by being quickly bundled out of the gallery and promptly offering Gorton an apology. To this day Alan Ramsey remains the only non-politician whose voice has been recorded by Hansard.

This image is taken from the House of Representatives Hansard, 9 March 1971. The member with the call was the Prime Minister, John Gorton. The interjecting voice was journalist Alan Ramsey.

William McMahon

Examples of the sort of everyday relationship some journalists enjoy with politicians is when they play sport together. When he was working with the ABC TV program This Day Tonight, Richard Carleton used to play squash with Billy McMahon, and was due to have a hit with him on the day McMahon deposed Gorton as Prime Minister.

“I knocked on the door, walked into McMahon’s office, to the new Prime Minister, and said, ‘Looks like we’re not playing squash.’

McMahon : ‘Oh, oh, ah, I’d say so. We’ll fix it though.’

I said: ‘Just so we’re all square, let’s go and do a quick interview.’

McMahon replied: ‘Oh, all right, all right, we better bring Sonia though.’

Carleton’s mental reaction to this suggestion was: You ****ing little ripper!” His actual reply was: “Oh, yes, I meant her, too.” – Richard Carleton.64

Despite having a close working relationship with many Gallery journalists, as McMahon had leaked a lot of material to them over several years, he was not respected by them at all.

“McMahon was ridiculed by the Press Gallery who viewed the man as a national embarrassment and cartoonists mercilessly lampooned him.”65

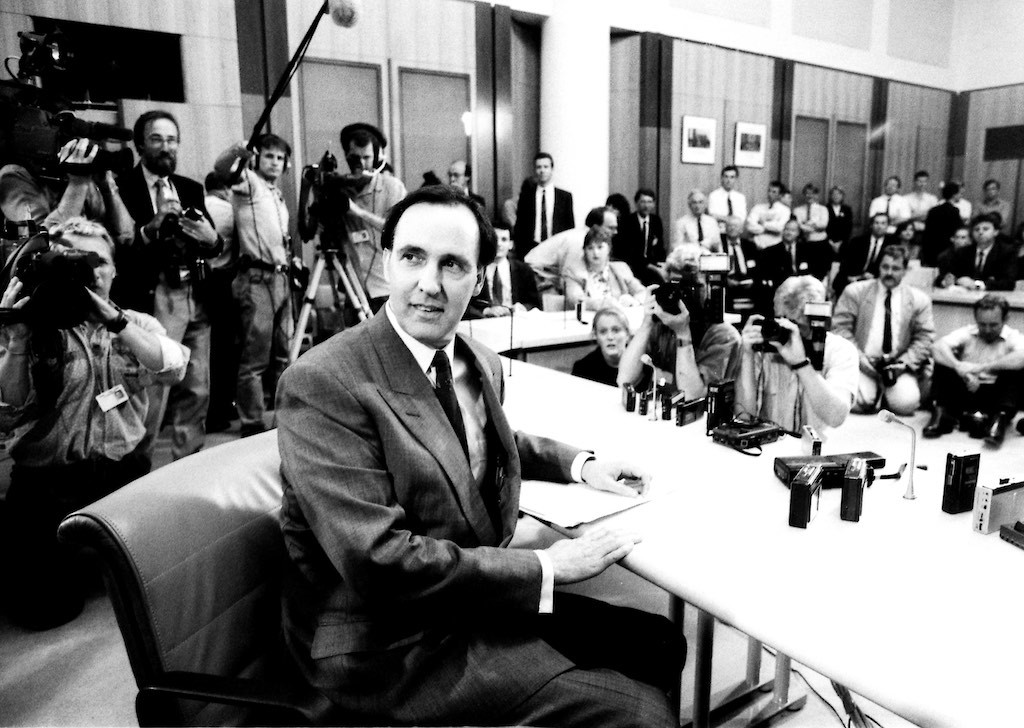

Prime Minister Bob Hawke speaks at a press conference in front of a number of radio reporters with both Nagra reel-to-reel and the more modern cassette recorders. The cameraman behind Hawke is shooting on U-matic, a large and cumbersome format where the camera was connected by cable to the recorder (which housed the tape). Photo: Fairfax.

Commercial radio networks started to make an impact under McMahon in 1972 although their equipment was very basic with station 2UW having just one tape recorder that played voices down a telephone line. The ABC’s AM and PM current affairs reporters, who had a presence in the gallery from the late 1960s, used reel-to-reel recorders. Unlike cassette recorders, these 10 kilogram portable monsters used 12 D size batteries and recorded excellent quality audio.

“McMahon once tried to steal a tape recorder from me. He borrowed it, then refused to return it, claiming: “It’s mine.” I had to walk into his office uninvited, grab the device from his desk and point to where the name of the radio station I worked for was engraved.” – Laurie Oakes, 2017.66

There were no permanent TV facilities in Parliament House until the very end of the McMahon government in 1972. The early 1970’s saw a new breed of Press Gallery members when television networks established studios, bringing with them camera and sound operators and technicians, all of whom were eventually granted full membership status in 1983. Channel 7 was the first network to have a permanent employee working at Parliament House, and Channel Nine was the first to have ENG cameras (portable news cameras shooting on tape) covering the House as well as a small studio. Ten and the ABC soon followed even though the ABC had established a large TV studio in Canberra in 1963 only 6 kms from Capital Hill.

“They [TV crews] seem to work out of a small caravan of station wagons which can usually be seen parked around the Parliament, adorned with the logos of various media groups… younger, more casual in their dress (they don’t have to enter those areas of Parliament where a coat and tie is still a necessary passport), they seem more inclined to turning their talents to making a surfing movie than [reporting]…on the latest developments in politics.” – Derek Woolner, 1976.67

Despite undertaking to have regular formal press conferences when he became Prime Minister, Billy McMahon reneged and rarely spoke to groups of journalists, not even for background briefings. Holt, Gorton and McMahon all tried to use the new medium of television to their advantage but none of them had the on-camera presence of Gough Whitlam. When Whitlam took over he held weekly pressers when he was in Canberra until they fell off in his final year.

“The press complained that many of McMahon’s speeches were not newsworthy, he held almost no press conferences, conducted few interviews and his press releases were often episodic and ad hoc.”68

Women in the Gallery

By December 2014 the Press Gallery had a strong showing of female journalists in its ranks including, from left to right: Sarah Whyte, Lauren Gianoli, Jessica Marszalek, Jane Norman, Rosie Lewis, Jennifer Rajca, Eliza Borrello and Susan McDonald. Photo: Matt Bulley.

One only has to look at the photos of the Press Gallery in the 1930’s and 40’s to see just how few female journalists there were in the early years. In fact there were just two recorded female members of the Press Gallery, Miss L. Denholm from the Sydney Morning Herald in the early 1930’s and Norma Jones from the Melbourne Herald in the mid 1930’s, before the Australian Journalists Association decided in 1941 that ‘the admission of women members to the Press Gallery is necessary in the general interests of the association.’69

Women have had to fight just as hard, probably harder, to achieve professional recognition in the Press Gallery as anywhere else in society. Working in a male dominated industry like the media would’ve been hard enough for trail blazing female journalists. Couple that with the male dominated environs of Parliament House and politics in general and it meant that it was several decades before women were seen in greater numbers in the Press Gallery. By 1981 there were 25 female Gallery journalists from 180 total Gallery members, and by 2015 that number had climbed to almost 100, or about one third of Gallery members. The only male dominated parts of the Press Gallery now are the photographers and cameramen/sound operators. This is likely due in large part to the weight of the equipment and physical nature of the work rather than ingrained chauvinism.

Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Overseas Trade in the Whitlam government, Frank Crean being interviewed by Gay Davidson in his office, 1975. Davidson was the first female Press Gallery President, when it had around 110 members, and first woman to head a bureau in the Gallery. Photo: Ian Mitchell, Australian Information Service, National Library of Australia nla.pic-vn4707205.

“The blokey culture of the Canberra Press Gallery never caused Gay Davidson [the first woman to head a Press Gallery bureau and the first female Press Gallery president] to pause. Indeed, at one point, she sought and obtained permission to use a male toilet, near her office in the Press Gallery, because the nearest women’s toilet, at that stage, was “too far away.” Gay explained, as she pressed her case, that there would be “no embarrassment” as most of the men in there would be “facing the wall.”70

“At that time [the mid 1980’s] there were sometimes snide comments if a female journalist got a story — somebody would say you got it because you were sleeping with someone, or something equally charming.

“The political views ascribed to you were actually ‘clearly’ those of your father/husband/boyfriend because, you know, a girl had no capacity to think for herself!” – Laura Tingle, 2019.71

Gough Whitlam

“Whitlam was always in command, retaining discretion to recognise journalists or ignore them, and to terminate the questioning at his pleasure.”72

“Most of his [Alan Reid’s] colleagues in the Press Gallery (especially the younger ones, most of whom were tertiary educated) seemed to be seized with an incurable affection for Whitlam.”73

“In the author’s experience, no party leader had better relations with Gallery journalists than Whitlam, and if they wandered into his office, they were welcome.”74

“[In press conferences, Whitlam ] often would not give the call to a journalist who had written something recently that offended him.”75

A typical newspaper office in the Press Gallery at Old Parliament House, where smoking was allowed and only two fingers were needed to type out a story. Photo courtesy of the Reid family collection.

Long since having passed its use-by date, Provisional Parliament House was bursting at the seams with an increasing number of politicians and media looking to be housed there. In 1974 the presiding officers ordered a stop to further expansion of the Gallery to prevent overcrowding as officials had already described it as a fire trap. Organisations such as SBS who arrived after 1974 had to set up an office outside parliament – a significant disadvantage to covering news when your contemporaries are in the same building as the action (SBS were eventually granted Gallery space in 1982).

Journalist Alan Reid described the Old Parliament House Press Gallery as “a rabbit warren of narrow dark corridors and dingy overcrowded rooms, cluttered with filing cabinets, clattering typewriters and teleprinters, untidy newspaper stacks, TV cameras and broadcasting equipment, and the general paraphernalia of the media industries.”76

A teleprinter was a machine where the typist sat in Canberra and typed while her material was being duplicated in another machine in Sydney or Melbourne, allowing for “practically instantaneous transmission of news.”77 Copy sent by telegram would take anything up to two hours to get to its destination, often missing deadlines as a result. The teleprinters were a welcome technology even though they were large and quite loud. Fax machines started replacing teleprinters from the 1970s.

“In today’s Gallery, AAP (Australian Associated Press) is in the worst situation, with two teleprinter operators sitting within a metre of up to six reporters typing out running reports of Question Time and proceedings. Before the introduction of quieter machines in 1980, the noise in the AAP office on a sitting day made it hard to carry on a conversation.”78

“You could hide nothing. You couldn’t have secret Cabinet meetings. You couldn’t have secret committee meetings. If a Minister was summoned to the Prime Minister’s office, the odds were he’d pass six journalists along the way.” – Colin Parks.79

“Every speech, every statement, every newspaper article has a potential significance, and the first to see it has a story… In the Press Gallery, intermingling is so frequent, intimate and unavoidable that journalists exchange not only information but accents, styles of speaking, styles of behaving, sexual partners and colds.” – John Edwards, 1973.80

The powers that be were very reluctant to allow TV resources into Parliament House and it took Channel Nine several years of negotiations to get a line installed to allow a studio camera signal to be transmitted out of the building. The Parliamentary authorities would not allow any sort of decoration in the studio, including screwing the backdrop to the wall. Former Nine Network journalist Michael Schildberger recalled “They finally allowed us to fix the backdrop after it fell forward and nearly brained some politician.”81

The August 1975 Press Gallery trip to Wattie Creek where PM Gough Whitlam (standing, 7th from right) famously poured a handful of soil into Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari’s hand. This photo was signed by Whitlam for 21 year old camera assistant Richard Michalak (standing, 8th from left) who is standing in front of the PM’s wife Margaret. For decades the prime minister of the day has traveled by air on a Royal Australian Air Force jet, often with a few members of the Press Gallery.

Whitlam was the first Prime Minister to really use television to his advantage and communicate with his audience effectively. His time as Prime Minister coincided with political television reporting starting to mature. But just as Whitlam shone on television, the medium allowed audiences to see more of their politicians, including his Treasurer Jim Cairns and the young and attractive staffer Junie Morosi. Their affair, pictured in the minds of voters through the TV set in their lounge room, was one of the many problems of the Whitlam government that led to his downfall.

“Television changed for all time the reasonably close relationship that had existed between individual journalists at Canberra and the politicians. Personal trust and understanding were still possible, but only on a private basis. One-man private interviews still occurred but the emphasis was on the mass interview, with the Prime Minister or one of his Ministers facing a battery of cameras, tape recorders and questioners. It became a matter of ‘beat the Press’ rather than ‘meet the Press’. Everything, every gesture, every nuance, every word, was for the audience, and the bigger the audience the better for the politicians. Such old-fashioned techniques as ‘off the record’ and ‘background’ went by the board.

The change had debits and credits. The camera enabled the public to see its politicians as they really were – their skill or ineptitude, their mental agility or their retardation, their knowledge or ignorance of the subject of which they were supposed to be master. It opened the way for a new type of journalism, whereby a sufficiently skilful interviewer could pin down his victim, and either extract information from him or reveal him in all his evasiveness and mendacity.”82

“Quite small and ineffectual demonstrations can be made to look like the beginnings of a revolution if the cameraman is in the right place at the right time.” – Gough Whitlam.83

One of the first television broadcasts of Parliament was the historic joint sitting after the double dissolution election in 1974. This photo shows a TV camera on the floor of the House of Representatives, below the public gallery on the left. The press gallery above the Speaker’s chair was so full of journalists it was standing room only. Photo source.

Parliamentary proceedings in the Houses had been broadcast on radio for nearly 40 years before approval was given for that same audio to be used in news bulletins. The Treasurer’s Budget speech and Opposition Leader’s right of reply were broadcast on television from 1984.

“The Whitlam government felt so aggrieved by the national media that in 1975 it seriously considered starting a national tabloid newspaper funded initially by taxpayers and then advertisers. It was to be run on editorial guidelines similar to the ABC.”84

Whitlam was quite a character, and those in the Gallery saw that first hand, including at unexpected times. The following story is retold by Brett Bayly, former journalist with The Advertiser.

Gough Whitlam often spoke in a deep, gruff voice that left you in no doubt who was speaking.

When he became Prime Minister in 1972, The Advertiser owned a house just 300 metres from The Lodge, the Prime Minister’s residence in Canberra.

One Friday morning I was out on the front lawn, collecting a weighty bundle of newspapers dumped there by some poor delivery guy who probably has a back problem today. It was that time of the week that I did not look forward to, writing my weekly column for Saturday’s paper.

These mornings were sometimes made more difficult because they followed the end of the two or three week Parliamentary session which meant party time in the Old Parliament House.

And so it was with some surprise as I slowly bent down, still dressed in my house coat, that I heard that voice: “Good morning Bayly!”

Looking up, there was Gough on the footpath, his security men sitting in a car 30 metres behind as the PM strode along the street. “Good morning Prime Minister,” I replied.

“Starting a little late this morning, aren’t we?” he said in a somewhat accusing tone. I explained that I did not go into the office until the afternoon to which he just grunted. Then, as was his manner, he just stood there and said “Well!”, as if you were expected to know what he was thinking.

“Well what?” I asked.

“Well aren’t you going to ask me in for a cup of coffee?” he replied.

This was getting a little weird, but due to the activities the night before I did have a pot of coffee brewing in the kitchen, and so I invited him to follow me in.

My lovely wife, Claudette, was still in bed when we entered the hallway. I called out: “Darling, you had better get up. We have a visitor.” To which she promptly and equally loudly replied as she got out of bed, reaching for her house coat: “Who would be stupid enough to visit at this time of the morning?”

Gough just stood there beaming as Claudette entered the passageway. Seeing his towering figure in front of her, she quietly reversed into the bedroom without a word.

We went into the kitchen and I poured two cups of coffee. There was a little small talk as Gough threw back the coffee in a few gulps and then looked at his watch.

“Well I guess I had better go. Somebody has got to run this country,” he said and so I escorted him to the front door. But then he paused and gave me another “Well!”.

“Well what Prime Minister?” I asked.

“Well what do you do when you come to my place (meaning The Lodge)?” he asked. The Prime Minister occasionally invited the media to The Lodge, usually just before Christmas.

“I drink your booze,” I responded.

“Yes, but what else?” Gough said while looking around him.

It was then that I realized what he was on about. I signed his visitors book.

“Exactly,” he said.

Just inside the adjoining lounge room was a small table, and on the table was my visitors book which my Editor insisted I keep as a record of my guests. I handed it to Gough and he opened it to a new page and scrawled E G Whitlam across the page.

He handed the book back to me and as he walked out the door, he turned and said to me: “Bayly, you are as pretentious as I am.” And with that he was gone.85

There was a bit of rivalry between news and current affairs reporters within ABC radio, the remnants of which was a “joke” line of masking tape running down the middle of the ABC office which was still there in 1980. On one side sat the news journos, on the other were the AM/PM current affairs reporters. The birth of the division in the office started in 1975 when a permanent landline was installed between Parliament House and Sydney, from where AM and PM were broadcast. The landline allowed the ABC radio news reports to be sent outside of the time slots set aside for their current affairs colleagues. On November 11, 1975, when Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was dismissed, the PM program decided to go live to air with a special broadcast, earlier than their usual time slot. This effectively hogged the one line that the news journalists used to get their stories out resulting in Sydney news journos holding a stop-work meeting and threatening industrial action.

The biggest day in Australian political history, 11 November 1975. Prime Minister Gough Whitlam waves to the gathered crowd of supporters while a throng of Press Gallery media is there to record it. Note that the cameras are all shooting on film. The 2UE journalist would’ve recorded excellent audio at that distance, had Gough said anything. Photo: Fairfax.

The tensions at the ABC extended to the television side too when the current affairs program This Day Tonight was gaining popularity with Richard Carleton reporting from Parliament. He was instructed by the ABC news chief of staff not to go into the ABC news office and instead had his own office on the other side of the building.

“I didn’t go in the news room… in fact I wasn’t allowed near the news room.” – Richard Carleton.86

Malcolm Fraser

“Fraser was anything but a popular Prime Minister in the gallery—most believing he came to power, if not by a conspiracy between the Governor-General and Fraser, at least by highly dubious constitutional means.”87

Such were the feelings between the Press Gallery and the Fraser government that the annual cricket match of pollies v media didn’t happen for the first three years of Fraser’s Prime Ministership.

Although Whitlam was the first PM to regularly use the doorstop interview technique, it was Malcolm Fraser who really perfected it. Fraser would rarely hold press conferences, preferring instead to get his message across to the media who would wait outside Parliament House in the morning. After one, sometimes two questions on the subject matter of the day, he would walk off into the secure area of Parliament House where the media could not follow. If the questions thrown were too hard or sensitive Fraser would simply walk straight through to the building without saying a word, a technique commonly used by many politicians in the years since.

Newly elected Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser waves to the gathered press at Old Parliament House two days after his election victory, 15 December 1975. Photo: Excapix.

“He [Fraser] never allowed himself to be tied down to regular press conferences.”88

“According to Derek Parker, one journalist noted that, “[Prime Minister] Fraser does not trust journalists to report what he says correctly. That, at any rate, is his excuse (for not holding general press conferences) although there are some in the Parliamentary Press Gallery who like to think that the reason is that newspaper journalists ask tougher questions than their electronic counterparts”.”89

“One of the problems is that everything a government does from Canberra gets filtered through the Press Gallery… I am sometimes accused of favouring television or radio. Well at least the words you use go over the medium, especially if you do it live.” – Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, 1982.90

Taken in mid 2015, this photo shows an example of where modern technology sits beside that which is long redundant, in this case Marantz equipment that recorded audio onto cassette. Photo: Nick Haggarty.

By 1981 there were 10 full time commercial radio journos in the gallery. Today that figure sits at four, with another person based in Sydney, traveling to Canberra only for the 18 or so weeks of the year when Parliament is sitting. Despite the space restrictions in many offices in the Gallery, some redundant equipment sits around for several years before finding a new home at the National Film and Sound Archive, or possibly ending up as landfill. With movement into and out of the Gallery and consolidation within media organisations happening on a regular basis, the space within the Press Gallery offices constantly changes.

“Without the possibility of leaks you really do have news management. I would also argue that governments – and our present government in particular – provoke leaks by being unduly secretive.” – Laurie Oakes, 1980.91

“Reporters who want to survive in the Press Gallery learn how to play politics as hard as the politicians. Politicians and the Press Gallery not only react to one another, they inter-act. The traditional role is for the Press Gallery to react to politicians, reporting events as they happen. Sometimes in a fast-developing crisis, politicians lose control and the Press Gallery sets the pace.” – Peter Bowers, SMH, 1981.92

“It began to dawn on the gallery towards the end of his occupancy of the Lodge that Fraser was by no means the snooty, old-fashioned Tory whose only mission was to keep Labor out of office. The author asked Barnett [Malcolm Fraser’s media advisor] why the gallery, including myself, was so surprised by Fraser’s record: the saviour of Fraser Island; an environmentalist; champion of multiculturalism; a key player in the overturning of white colonial rule in Rhodesia; a fierce opponent of apartheid in South Africa; not to mention his tireless opposition, in retirement, to the central tenets of John Winston Howard. Barnett’s observation was that it illustrated ‘the great depth of superficiality of the Canberra Press Gallery’. ‘They looked at this bloke’, Barnett continued, ‘they considered his background, and they allocated him to a pigeonhole’.”93

Indigenous People in the Gallery

For many decades the Gallery consisted almost entirely of people from Caucasian backgrounds. Then in 1983 the first indigenous journalist arrived in the form of 20-year-old Stan Grant. Having snagged a job with The Canberra Times, Grant struck up a friendship with another young journalist, George Megalogenis. Coming from a Greek background, Megalogenis’ olive complexion meant he and Grant stood out among the white faces and the two used to joke that they “were the blacks of the Gallery!”94

Grant’s time in Canberra coincided with Australia’s first indigenous federal politician Neville Bonner’s time in the Senate. Bonner was aware of the significance of Grant’s position as an aboriginal journalist and took Grant under his wing.

“Neville Bonner was like an uncle – he used to look out for me.” – Stan Grant, 2017.95